Introduction

Recognizing that societal challenges, such as climate change and social inequality, are systemic in nature, transition studies has called for public policies that promote socio-technical systems innovation (Schot and Steinmueller 2018). As synthesized by Weber and Rohracher (2012), the rationales for such transformational policy interventions are multi-faceted market failures (derived from economics), structural system failures (derived from innovation studies) and transformational system failures (derived from transition studies). At the same time, transition scholarship has recognized the contested political nature of transition processes (Meadowcroft 2011) which can impede the adoption of transformative policy mixes (Kern and Howlett 2009, Rogge et al 2017). Investigating the policies and politics of transitions has therefore been a key line of research in transition studies (Markard et al 2012), reflected for instance in the research agenda of both the Sustainability Transitions Research Network (STRN) and the annual conference on International Sustainability Transitions (IST). Correspondingly, transition scholars have investigated how to deliberately steer and accelerate systemic changes towards sustainability (Geels 2014, Kern 2015, Robert 2018). They have also pointed to the dual politics of transitions arising from, on the one hand, resistance from incumbent actors entrenched in the declining trajectory and, on the other hand, contestations around designing the new “rules of the game” in the emerging, potentially more sustainable trajectory (Rogge and Goedeking 2024). This line of research on the policies and politics of sustainability transitions is sometimes summarized under the umbrella of governing transitions, and consists of multiple and evolving fields of investigation on when and how to intervene in transition processes (Koehler et al. 2019).

Early work suggested a rather discrete albeit important role of interventions in transitions processes, focused on industrial policy, procurement and regulation (Kemp, 1994). This view expanded to interventions in the different stages of a transition process and the role of governmental authorities within each stage, for which two key approaches were developed. One of them is Strategic Niche Management (see chapter 5) which focuses on early transition stages (Kemp et al. 1998). The other concerns Transition Management (see chapter 3) which proposes a long-term view on interventions in each transition stage (Rotmans et al., 2001). These developments were further nurtured by considerations of reflexive governance (Voss, 2006).

Later research has delved into the notion of policy mixes, i.e. the combination of policy strategies and instrument mixes for steering and accelerating sustainability transitions (Rogge and Reichardt, 2016). Two key insights from this policy mix literature (Rogge 2019) include the importance of adopting policy mixes for creative destruction which are simultaneously supporting sustainability innovations and destabilizing unsustainable regimes (Kivimaa and Kern, 2016) and the importance of the credibility and consistency of policy mixes for driving transformative change (Rogge and Schleich 2018, Rogge and Duetschke 2018). In addition, policy mix scholarship has increasingly pointed out the importance of investigating policy-making processes and has called for drawing on the policy studies literature to better investigate the politics of policy mixes (Kern et al. 2019, Kern and Rogge 2018). This has led to new interdisciplinary developments, including a greater focus on policy feedbacks (Edmonson et al. 2019, 2020), investigations of the role of advocacy coalitions for policy change (Markard et al. 2016, Schmid et al. 2020, Gomel and Rogge 2020) and analyses of the multiple streams of problem, policy and politics to unpack the politics of transitions (Norman 2015).

In this chapter, we follow this call for better bridging transition studies and policy studies for investigating how public authorities can accelerate transitions towards more sustainable systems of production and consumption through transformative policy interventions – and refer to chapter 16 for a deep-dive on the politics of and power in sustainability transitions (Avelino and Wittmayer 2016, Avelino et al 2016, Avelino 2015).

Transition studies shares with policy studies a sense of urgency to understand and inform public policy in response to societal challenges. To address these challenges, scholars in transition studies have called for policy interventions promoting socio-technical change through addressing different intervention points (Kanger et al. 2020), whereas those in policy studies have similarly called for policies with transformational aims (Derwort et al. 2021). These calls are reflected in policies such as the European Green Deal, which seeks to tackle the climate crisis through low-carbon innovation (European Commission 2021). We argue that investigating how public policy can help achieve such transformational aims can best be addressed by bridging insights from both transition studies and policy studies: while the former has explored interventions for transformations towards sustainability, the latter has studied policy change – including its mechanisms and causes. Yet, despite calls to bridge both fields (Kern and Rogge 2018, Roberts et al 2018), with a few exceptions transition and policy studies remain largely unconnected.

On the one hand, transition studies with its fundamentally systemic perspective offers insights on how to steer system transformations while recognizing the complex and uncertain nature of socio-technical change (see the various contributions in this handbook). The field has experienced tremendous growth over the past two decades (Zolfagharion et al. 2019; Hansmeier et al. 2021). It emerged from innovation studies to investigate the occurrence and dynamics of change associated with socio-technical transitions (Geels 2004), broadly defined as major shifts in systems fulfilling societal functions, such as energy or mobility. Such shifts require deliberate steering towards societally desirable outcomes (Grin et al. 2010; Weber and Rohracher 2012). Research has studied “the preconditions, driving mechanisms, broad patterns and possibilities for accelerating radical transformations” (Kanger et al. 2020); developed several analytical frameworks for analyzing these conditions, mechanisms, and patterns (Markard et al 2012); and has formulated policy recommendations on how to advance sustainability transitions (Geels et al. 2019; EEA 2019; Kern et al. 2019).

On the other hand, policy studies has researched policy change. For a long time it differentiated between two basic kinds of change: (small) incremental (Lindblom 1959) versus (major) paradigmatic policy change (Hall 1989, 1993). This basic differentiation suggested that policymaking is often characterized by long periods of relative stability followed by short periods of significant shifts triggered by exogenous shocks (Baumgartner and Jones 1991, 1993). This orthodoxy was later challenged by Howlett and Cashore (2009) who argued that paradigmatic policy change can also come about endogenously: many incremental changes in the “same direction” can over time culminate in paradigmatic shifts. These conceptual frameworks have significantly refined our understanding of policy change. However, they do not capture or explain system transformations to sustainability more generally, in part because they typically do not address how these transformations could be deliberately steered (Berglund et al. 2022).

Given the significant potential for interdisciplinary collaboration between transition studies and policy studies, our guiding question for this chapter is: Which policy interventions help accelerate sustainability transitions, and under what conditions do they work? Following the realist synthesis (Pawson et al., 2005), we structure our chapter in four theory areas for which empirical insights are widely available: (1) directionality, (2) niche support, (3) regime destabilization, and (4) coordination. We selected these areas because they are comparatively mature, building on extensive empirical and conceptual work in transition studies (for further details on our methodological approach, see the online supplementary material). By presenting transition studies insights on key policy interventions for these four theory areas and by offering potential connections to policy studies, we ultimately aim to spark new interdisciplinary research bridging both fields.

2. Bridging four theory areas from transition studies with policy studies

In the following, we introduce four key theory areas in transition studies, together with their relevance for transformational policy interventions, and reflect upon conceptual overlaps with policy studies (for an overview, see Table 1): (1) providing direction to transformations (directionality); (2) creating and protecting novelty (niche support); (3) destabilizing the status quo (regime destabilization); and (4) coordinating such processes (coordination).

Table 1 Four main theory areas in transition studiesz

Theories areas | Mechanisms | Explanation |

Directionality |

| Transitions follow certain directions and not others. Thus, they result in different outcomes. Policy interventions in this theory area intend to guide a transformation towards particular ends. Society is expected to be actively engaged. |

Niche support |

| Innovations in early phases are likely to fail due to their incompatibility with existing systems. Interventions in this theory area intend to strengthen innovations so that they can compete with dominant practices. |

Regime destabilization |

| The status-quo demonstrates path-dependence, has embedded internal logics, and is supported by configurations of elements that are difficult to change (e.g., regulations, organizations, etc.). Transition scholars advocate for policy interventions that weaken these configurations. |

Coordination |

| Transformations are long term and multi-dimensional. Thus, policy consistency is necessary in different policy domains over time. This harnesses synergies and increases the chances of policy success. |

2.1 Directionality

The first theory area refers to how transitions can be directed towards particular ends (Andersson et al. 2021). This focus in transition studies is being picked up by innovation studies scholars who until recently were primarily concerned with rates of technological change – as a driver of economic growth and competitiveness – rather than its direction. The direction of innovation processes was long assumed exogenous to the processes themselves, or – more precisely – was left to be determined by market forces and/or scientific paradigms. This inattention to the direction of technological progress, however, did not guarantee its alignment with collective societal goals (Rotmans et al., 2001, Loorbach et al., 2017). For this reason, transition studies scholars have stressed the need to define the most societally desirable routes for innovation, indicated for example by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Defining such directions has been referred to as transformation directionality (Weber and Rohracher 2012).

By extension, the governance of directionality refers to the deliberate selection of societal priorities and the active steering of system transformations towards these desirable outcomes (Garud and Gehman 2012). One prominent example of low-carbon directionality is the societal prioritization of renewable energies over fossil fuels. Defining the direction of a transition is a deeply political process, as any change generates winners and losers. For instance, when policymakers prioritize urban low-carbon mobility solutions, they do not only favor green innovators and new low-carbon business models, but thereby equally challenge incumbents centered around private vehicle ownership. These benefits and costs extend to inter-connected industries, such as infrastructure providers, manufacturers, traffic managers and users.

Given the contested nature of transformational change, transition studies has proposed mechanisms to deliberate and provide such direction, for instance by creating shared visions and expectations. Transition management has proposed setting up networks in which actors can deliberately define transformation pathways (van der Brugge et al. 2005). Pathways can be defined in broad terms, as the societal challenges that policies ought to address (Weber and Rohracher 2012) or as missions to be supported by policies (Kattel and Mazzucato 2018). By establishing sustainability as a desired direction of transitions – and breaking this overarching objective down into more concrete goals – policymakers can enable a common vision for actors that can serve as a guidepost for consistent policy mixes (Rogge and Reichardt 2016). Such policy mixes, in turn, can provide strong signals of policymakers’ commitment to a specific direction (Rogge et al. 2017).

Policy studies frameworks, bar exceptions (Howlett and Cashore 2009), do not explicitly deal with or account for directionality. The Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF), for instance, principally provides a conceptual toolkit for capturing, describing, and explaining how policy change comes about. The ACF does not grapple with questions pertaining to whether certain policy outputs and outcomes are somehow ‘better’ or ‘more desirable’ than others (Pierce et al 2017; Weible et al 2011). The attention given to directionality by transition studies could therefore be a valuable contribution to the field. For example, directionality could serve as a heuristic to uncover the societal course underpinning specific policy changes and impacts. By making explicit the question of what pathways of societal change should or should not be chosen, directionality could prove to be a useful conceptual addition to research on agenda setting and questions around how and under what conditions societally desirable issues remain on the agenda. Likewise, directionality could serve as an additional evaluative criterion for classical policy impact analyses, alongside traditional metrics such as effectiveness, efficiency, and political feasibility.

Policy studies, in turn, can offer transition studies an analytical toolbox for capturing, describing, and explaining the contested nature of policy processes underlying and giving rise to directionality. Alongside insights from classical policy models, such as the ACF (Markard et al 2016), the investigation of directionality has already started to benefit from research on policy feedback (Edmondson et al 2019, Schmid et al. 2020) and strategic sequencing of policy (Meckling et al. 2017; Pahle et al. 2018). Policy studies might also ask how and under what conditions the direction of a societal transformation can be deliberately steered in the first place, drawing on lessons from non-rational policy models that emphasize the messiness and chaotic nature of policymaking, such as the garbage can model.

2.2 Supporting novelty creation

The second key theory area of transition studies relates to novelty creation and the origins of transformative innovations in niches. Examples of protected spaces include industrial niches, niche markets, and confined communities such as eco-villages. Experimentation in such niches can be a major driver for novelty and learning (Sengers et al., 2019). However, transformative innovations emerging within these niches often follow logics incompatible with the status-quo that sets ‘the rules of the game’ and is referred to as ‘the regime’ by transition scholars (Smith and Raven 2012). Put differently, radical niche innovations are typically not well aligned with the practices, institutions, and rules that characterize the existing socio-technical system (Geels 2004). Such misalignment is particularly visible in the early stages of an innovation. For instance, electric vehicles were originally incompatible with fossil fuel-based private vehicle transportation because of limited charging infrastructure and distortionary fuel taxing. Similarly, autonomous vehicles operate under legal loopholes and fully-automated driving may be considered illegal based on international road conventions (Salas-Gironés et al, 2019). Thus, transformative innovations often to do not easily align with existing systems. Together with limited resources and resistance from vested interests, radical innovations are therefore likely to fail (Kemp et al. 1998).

Drawing on evolutionary economics, transition studies scholars have advocated for transformational policy interventions that protect niches, suggesting that niches are ‘variation environments’ but unfit for selection pressures (Kemp et al. 1998). Protection occurs through mechanisms of ‘shielding’, protecting novelty from external pressures; ‘nurturing’, improving its performance; and ‘empowering’, facilitating its diffusion (Smith and Raven 2012). Interventions aimed at novelty creation allow the building of networks and shared expectations (Kivimaa 2014), provide the sufficient conditions for cumulative causation (Jacobsson 2004), and facilitate learning, e.g. in terms of price performance or user preferences (Schot et al. 1994).

Policy interventions supporting radically different ideas that break with the status quo invite interdisciplinary research on what might be termed ‘novelty policymaking’: research which combines novelty conceptualizations and interventions from transition studies with policy analysis approaches from policy studies. While transition studies could thus open a new research avenue for policy studies (Raven et al. 2016), policy studies could offer transition studies a suite of concepts to further unpack the politics of novelty creation (Ruggiero et al, 2018). Moreover, policy studies could present a cannon of research on how and under what conditions novelty spreads across jurisdictions, for instance through policy diffusion (Trachtman 2021).

2.3 Destabilizing the status quo

At their core, socio-technical systems are characterized by stable configurations of industrial complexes, economic arrangements, political structures, technologies, infrastructures, knowledge, markets, user practices, and institutions (Smith and Raven 2012), which are reinforced by cognitive, normative, and regulative rules (Geels 2004). Since transformative niche innovations are often incompatible with these existing systems, their wider diffusion and associated system transformations are typically hampered. Without policy interventions or external shocks or trends, such as war or digitization, transformative niche innovations often only unfold slowly, if at all (see chapter 7). For example, it has taken renewable energy several decades to take off, despite persistent policy support. This relatively slow speed can be partially explained by the different logics underpinning clean energy technologies and the status quo (decentralized, renewable, small-scale versus centralized, fossil fuel-based, large-scale energy systems). Some rapid transformations have taken place, however, particularly triggered by external shocks (Johnstone and Schot, 2022), demonstrating that transformative societal change is achievable in short time periods.

Based on this insight, the transitions literature suggests a third area of policy interventions to accelerate transitions, namely to weaken dominant (and often unsustainable) regime technologies and practices. Weakening dominant systems creates space for the diffusion of promising niche innovations (Kivimaa and Kern 2016, Rogge and Johnstone 2017). The main purpose of policy interventions in this area is to reduce the inertia, path-dependency, and lock-in of existing systems (Rotmans et al. 2001; Kern and Howlett, 2009). Following Kivimaa and Kern (2016), who have emphasized the need for ‘creative destruction’, and Kivimaa et al. (2017) this destabilization can be achieved with policies targeting five functions: putting checks on unsustainable regimes through control policies such as carbon pricing; adjusting the playing field against existing dominant practices; reducing support for dominant regime technologies; changing social networks and replacing key actors; and changing practices leading to greater policy coherence.

Policy interventions destabilizing the regime predictably trigger fierce resistance from powerful vested interests. This explains why many real-world policy mixes are biased towards promoting ‘creation of the new’ over ‘destabilization of the old’. Transition research has already started to benefit from policy studies approaches to better understand the contestation of regime destabilization (e.g. Markard et al, 2021). Ongoing debates in policy studies of relevance for transition studies include, for instance, the politics of phase-out policies (Meckling and Nahm 2019), such as moving away from fossil fuels subsidies, coal, and internal combustion engines vehicles. Moreover, transition debates on inertia, path-dependency, and lock-in raise questions about regulatory capture and the strategic behavior of powerful business actors influencing or coopting regulatory processes (Meckling 2015), thereby potentially jeopardizing the adoption of stringent regime destabilization policies. Policy studies scholarship could equally ask what the institutional limitations of destabilization are, drawing on classical political science work on institutional checks and balances, and the institutional foundations of regulatory commitment (Levy and Spiller 1994; Henisz and Zelner 2006).

2.4 Providing coordination

A final key theory area of relevance for transformational policy interventions acknowledges that transitions are multi-dimensional processes (Weber and Rohracher 2012): they encompass diverse policy fields, call for cooperation between and among organizations, and benefit from policy coordination. For instance, low-carbon mobility depends on developments not only in the transport sectors, but also in energy, health, and information and communications technology. Without orchestrated policy interventions, conflicting policy signals can lead to delays and inefficiencies in transition processes. Transition scholars have thus argued that policy interventions should be consistent over time, in line with requirements of corresponding transition phases, and well aligned with overarching policy mixes (Rotmans et al. 2001; Reichardt et al., 2018; Meadowcroft and Rosenbloom, 2023).

For this reason, calls have been made to harness greater consistency of policy interventions by increasing coordination efforts, while acknowledging the limitations of such coordination (Flanagan et al. 2011; Rogge and Reichardt 2016). Multi-dimensional socio-technical transitions can be guided by overarching long-term policy strategies, targets, and roadmaps. Such long-term guidance is particularly effective when policymakers highlight their credibility by implementing consistent policy interventions to achieve long-term targets (Rogge and Dütschke 2018). Weber and Rohracher (2012) suggest three dimensions of policy coordination: coordination across different systems, across institutions, and regarding the timing of policy interventions (see also Kanger et al. 2020).

Here too we see fruitful avenues for bridging policy and transition studies. For instance, policy studies might draw on conceptualizations of multi-system transitions in its research on policy coordination (Rosenbloom 2020, Kanger et al. 2021) and investigate coordination requirements at different transition phases, such as early versus mature stages (Kivimaa et al. 2019a). Transition studies, in turn, could leverage insights from policy studies on policy sequencing and how to strategically grow coordination capacity over time (Meckling et al. 2017), as well as on the administration of policy mixes through various governing entities (Song et al. 2023). Transition scholars will also benefit from existing research on how different governance approaches can help overcome coordination challenges. Most notably, this includes work on collaborative governance (Scott and Thomas 2017; Florini and Pauli 2018), deliberative governance (Elstub et al. 2016), and institutional collective action (Kim et al. 2022). Likewise, policy studies research on experimental governance might offer valuable insights on how to generate cooperation around contested policy objectives. Since transition studies already offers a burgeoning literature on experimentation (Sengers et al. 2019; Kivimaa and Rogge, 2022), a first step would be to systematically contrast and compare both fields’ approaches regarding experimentation.

3. Synthesizing insights on transformational policy interventions from empirical transitions research

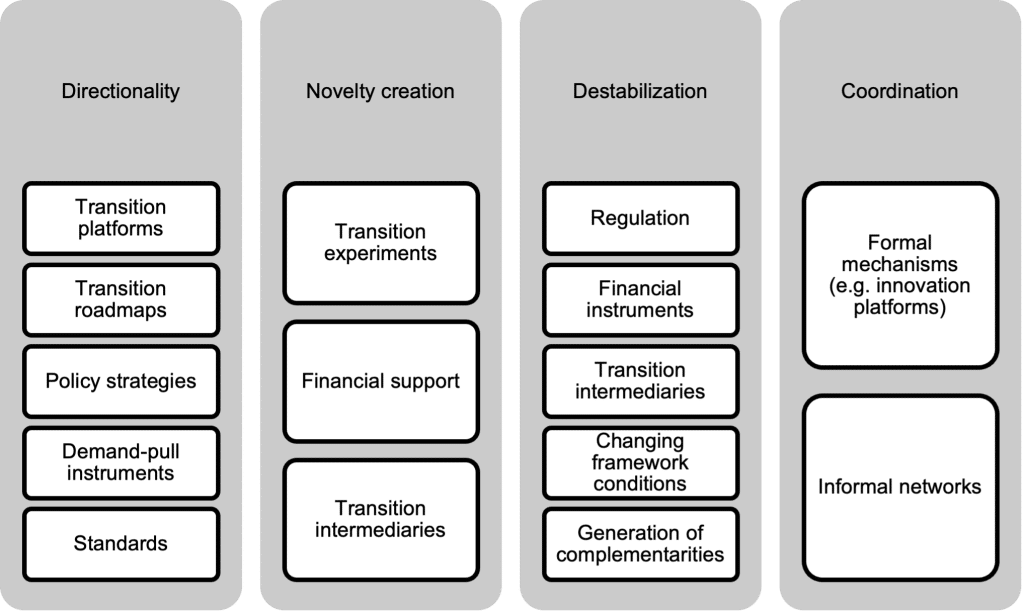

In this section, for each of the four theory areas we summarize and assess the policy interventions proposed by the transitions literature on how to accelerate system transformations (see Figure 1). To facilitate readability, references are cited as [JOURNAL ABBREVIATION#].

Fig. 1 Overview of transformational policy interventions suggested by transition studies

3.1 Insights on directionality

To provide directionality for system innovations, transition studies primarily proposes the following interventions: transition platforms, transition roadmaps, policy strategies, demand-pull instruments, and standards.

First, transition platforms are consultation arenas in which actors are brought together to develop common visions for transformations, with one of the intended outcomes being their acceleration. Such platforms are typically organized around specific topics. For instance, in the Dutch energy and mobility transitions, platforms were set up on topics such as interoperability, safety, and electromobility. Experts were invited to offer their insights on specific topical areas. For example, IT companies supplied expertise on interoperability whereas insurance companies provided insights on liability [SPP4, EIST37]. However, such platforms run the risk of excluding relevant stakeholders [TFSC6] and being coopted by vested interests [PS1], which raises issues around accountability [SPP3].

Second, transition roadmaps are generally the outcomes of transition platforms. Roadmaps are tools that couple expected changes for system innovation with certain technologies, milestones, and timeframes. For instance, roadmapping the electrification of the mobility system calls for selecting technologies, standards, and goals, such as a percentage of sales of electric vehicles by a given date [TFSC1]. Such roadmaps outline the expertise, visions, needs and industrial capacities of invited stakeholders of a given innovation system [EIST10, EIST19]. For example, Dutch roadmaps have placed major attention to IT developments because the IT sector is a strong domestic industry in the Netherlands [SPP4]. While developing roadmaps, policy actors face the risk of choosing underperforming technologies or those based on vested interests, and thus defining inadequate pathways and devoting resources to less urgent problems [EIST6].

Third, the design and pursuit of such socio-technical transition roadmaps should be aligned with and supported by overarching as well as context-specific policy strategies that provide direction. They can be seen as blueprints or ’master plans’ for a transformation’s expected goals and pathways. For instance, the UK’s ‘Zero Carbon Homes’ strategy provided guidance for the UK’s housing transformation [EIST39], and the Transition Management Project provided direction for the Dutch energy transition [PS1]. Such strategies are generally accompanied by task forces that facilitate increased operational capacities [SPP4, EIST39]. On their own, however, such strategies are insufficient to substantially accelerate transformative change, as they require the design and adoption of suitable instruments to achieve agreed upon targets. That is, they can fail due to a range of feedback effects arising from policy implementation difficulties and contestations, as well as unexpected exogenous conditions, such as financial crises [EIST39].

Fourth, a key type of instrument which can support the achievement of policy objectives and targets laid out in policy strategies demand-pull instruments can tilt the direction of a system innovation towards desired outcomes. This has occurred, for instance, when public authorities require electric vehicles in tenders for public transport [SPP1, SPP4, TFSC11] and in vehicle automation [SPP4, TFSC2]. Tilting demand generates incentives for actors to align their business models in certain directions. Actors may not be capable of achieving such alignment (for example due to technical reasons or knowledge), which could negatively affect industrial capabilities [EIST1].

Finally, standardization can also provide direction. Standards accelerate market developments by defining a common set of rules and procedures. Standards can be voluntarily agreed between market parties, but they can also be the result of public action. The adoption of electric vehicles has been stimulated by standardized charging points [TFSC3, TFSC4]. Furthermore, European standards have been developed around autonomous vehicles to favor their fast diffusion. The history of technology has shown the central role of technological standards in fields such as electricity markets, digitalization, and mobile communications [RP3].

In light of this evidence, providing directionality to transitions seems to demand strong state-led support. This can be a demanding task for policymakers. Directions must be clearly defined yet also be open to discussion and debate. Also, given inherent uncertainties of transitions, they must remain amendable to change. Studies call for a facilitating role of public actors to define visions and roadmaps necessary for achieving transformations [SPP3, SPP4]. Finally, major shocks, such as nuclear accidents, can facilitate transitions [RP1].

In providing directionality, policy actors need to deal with constant tensions between normative transformation goals and traditional policy goals such as economic growth. Thus, a transition may be ‘de-routed’ in favor of market-based solutions incompatible with societal needs. Additionally, selecting directions may lead to early lock-in and path-dependence [TFSC4]. This may have negative effects in the long term, e.g. when selected innovations outperform non-selected ones in the long run. Important questions of relevance for policy studies include how and by whom visions underlying transformations are crafted, influenced, and contested. Here we see a potential connection with policy studies frameworks, such as on procedural instruments, policy formulation, and coalition politics. Theories from policy studies can also enrich our understanding of how and by what means political actors attempt to define directions. For instance, the Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF, Sabatier and Weible, 2019) has been used to explore how networks of actors’ shape policy developments in areas such as energy [EIST33], and the Multiple Streams Framework (MSF, Zahariadis, 2019) has been utilized to explore how institutional entrepreneurs shape policy directions [TFSC9].

3.2 Insights on novelty creation

To support novelty creation we identify transition experiments, financial support, and transition intermediaries as particularly well studied transformational policy interventions.

First, transition experiments are initiatives to explore new ways in which societal functions can be fulfilled. Examples of these experiments include energy communities [ERSS2] or low carbon mobility projects [RP9]. While experiments have generally local scales (such as neighborhoods), they are carried out with the expectation, if successful, to be replicated and/or diffused at a larger scale. Experiments are generally carried out in portfolios rather than in isolation [RP4]. This occurs because the outcomes of innovation processes, by definition, are uncertain. Successful experiments can be used as footprints for replication, adopted by incumbent players, or converted into spin-offs [EIST29]. In contrast, failures offer opportunities for learning. Institutional barriers and social contexts are major barriers for replicating experiments [EIST8]. Actors commonly opt for experiments with short-term returns, although results may take a long time [PS1, SPP5]. This is disadvantageous as societal challenges require both short-term as well as long-term improvements [SPP5].

Second, financial support offering economic incentives are major drivers of novelty creation but are not always present. Financial support allows public authorities to incentivize novelty creation through rewards. Transition studies literature distinguishes between entrepreneurial actors who generally require financial support to kick-start their own ideas, and those joining at later stages, seeking tangible economic benefits [EIST3, EIST18]. Financial incentives are important because returns on investment may occur only in the long-term [RP7], such as in carbon-capture technologies [EIST29]. For public authorities, two main challenges associated with financial incentives include budget constraints and limited experience on how to assess experiments’ performance [EIST3].

Finally, novelty creation is fostered by transition intermediaries, and thus policy support for such intermediaries is another policy intervention. Intermediaries’ activities include connecting actors (e.g. producers, users, entrepreneurs, and funding bodies), mobilizing skills, knowledge, and resources, and supporting specific technologies or goals (Kivimaa et al, 2020). In addition, intermediaries’ activities are also intended to have policy and political effects beyond novelty creation (see Kivimaa et al., 2019b). Empirical research suggests that intermediaries’ activities enable knowledge exchange [RP5]. This occurs, for example, through the aggregation of learnings from different initiatives [EIST32]. They are relevant for novelty creation because actors may otherwise be unaware of initiatives with similar goals and because the actor network from whom support and knowledge could be drawn is not necessarily visible [EIST16]. The role of such intermediary actors is not to create initiatives but rather to facilitate cooperation amongst existing stakeholders [EIST8]. Cooperation can be facilitated if intermediaries focus their support for projects on knowledge diffusion activities, such as networking [SPP6]. A main difficulty for these organizations, however, is the lack of long-term financial support and shifting policy priorities [EIST8]. Lack of user involvement tends to have a significant negative impact on their effectiveness [EIST28]. Transition intermediaries also generate important visibility and awareness for a transformation [EIST3], which can motivate new actors to join promising developments [EIST16, EIST6].

Policy interventions for novelty creation also face several difficulties. They have limited effects if beneficiaries lack skills or (human) capital to benefit from them [EIST15]. Experiments can be difficult to replicate in the presence of policy failures, particularly if they come with high political costs to policymakers [EIST22]. Another difficulty is that new policy interventions may be hindered by existing arrangements, as actors sometimes have limited ‘room for action’ due to regulations [EIST2, EIST3]. Furthermore, simplicity is a key factor of success. If requirements for policy interventions are too complicated, actors may opt to drop out or never engage [EIST25]. Actors may also refuse to participate in projects if they demand too radical changes in their organizations [EIST9], if benefits are unclear [EIST3], or if returns are limited [EIST4]. The absence of formal evaluations and assessments seems to limit the capacity for learning and diffusion [EIST8].

A key question raised within transition studies concerns the role of incumbent actors in novelty creation. For instance, in the case of low-carbon mobility, what should be the role of the automotive industry? While there is no clear-cut answer to this question, research has shown mixed effects, in which incumbents may both accelerate or undermine the speed and direction of transitions [EIST19, SPP4].

3.3 Insights on destabilizing the status quo

For facilitating the destabilization of the status quo, the transitions literature suggests a variety of transformational policy interventions (Kivimaa and Kern, 2016). More specifically, regulation, financial instruments, transition intermediaries, changing framework conditions, and generation of complementarities play important roles.

First, regulation can accelerate transitions by destabilizing the status quo. Regulations – or their amendment – create new or changed ‘rules of the game’ to which actors need to adapt (Unruh 2000). Such regulations can put pressure on the system, for example, with legal mandates, such as requiring the housing sector to adopt new technologies in the construction process [EIST7]. Such provisions can be negotiated with incumbent players to improve their buy-in, although this also increases the risk of less stringent regulations. As demonstrated by the German nuclear phase-out, regulations providing a phase-out trajectory for societally undesirable technologies can increase the credibility of policy mixes and thereby be highly influential for creating a market space for innovations and their diffusion, such as renewables [ERSS1].

Regulations alone, however, tend to be insufficient for destabilizing existing systems. Transition studies therefore also calls for changes in the incentives faced by investors, including incumbent actors, through financial instruments. For example, policy actors can accelerate the phasing out of an existing technology or practice by cutting back preferential loans or tax credits given to producers or consumers [EIST1, RP5, EIST27]. Such instruments induce market parties to shift their existing practices, product portfolios, and business models [EP1].

Third, transition intermediaries do not only facilitate novelty creation, but also help destabilizing the status quo [EIST37], and as such are considered as potential policy intervention. Intermediaries activities facilitate interaction between incumbent and emergent actors to support innovative processes [EIST14]. They are also used to create advocacy coalitions for change [RP5]. They can work better when radical views are incorporated into decision-making mechanisms, such as innovation councils [EP2]. Such policy intermediaries address both new entrants to generate radical innovations with transformative potential, and incumbents [EIST14], as without gaining incumbent support these innovations are more likely to fail due to system incompatibility [EIST13]. An example for this is the integration of new mobility solutions into well-established systems, such as public transportation.

Fourth, destabilizing the status quo can also be achieved through changing framework conditions defining how socio-technical systems operate. In recent years, strong attention has been given to environmental concerns, thereby replacing previous approaches that prioritized modernization and industrialization. Such shifts affect how systems operate and change. For instance, the promotion of a European green agenda has forced emission reductions in industry. Such changes have effects on transitions that are similar to external shocks, like the 1970s oil crisis. Changing conditions can also be achieved by new institutional arrangements, such as the responsibility of ministries area modified. For instance, this occurred when the United Kingdom’s Ministry of Agriculture took on new functions of environment and food policy [RP2] or when the Dutch Ministry of Infrastructure took over environmental functions [SPP4].

Finally, systems can be gradually changed through the generation of complementarities between existing systems and novelty. This can be seen in ‘last mile’ mobility options, such as public bicycle schemes near public transport. They do not represent a direct confrontation with existing mobility systems, but rather allow coexistence of old and new features. Such complementarities can be in terms of infrastructure [EIST6], capital [EIST20], or user practices [EIST18]. Complementarities can be seen as ‘windows of opportunities’ for existing industries. For instance, many Dutch high-tech companies supported mobility changes because they observed a window of opportunity for new markets [SPP4]. The transition speed seems to be associated with such perceived benefits [EIST36]. Incumbents’ acceptance increases when tangible benefits are present [EIST30, SPP5], whereas transformations are less likely to occur if changes are too radical for users, producers, and consumers [EIST6, EIST28].

Policy interventions aimed at destabilizing regimes face several challenges. For example, political tensions arise when societal and economic goals are incompatible [EIST15]. This may result in contradictory objectives and thus inconsistent policy mixes aimed at, for example, ensuring competitiveness of existing fossil-fuel based industries while expanding the share of renewables. Intentional regime destabilization can come to a halt due to sudden political changes [EIST12], unsuccessful experiments [EIST22], and lack of positive feedbacks for system change [RP8].

To date, there are several pressing questions to be answered by transition studies scholars that would benefit from a collaboration with policy studies–. First, how, when, and why are destabilization policies politically feasible in democratic political systems, especially when elected officials must fear backlash against too radical policy change? Second, how can regime destabilization policies complement approaches that favor the emergence of a new socio-technical regime? Public acceptance of a regime change likely depends on the widespread expectation that new regimes are beneficial to society (Lennon et al, 2019).

3.4 Insights on coordination

Transition studies suggest both formal mechanisms and informal networks are relevant for accelerating sustainability transitions.

First, formal mechanisms include innovation platforms. They can support transitions, particularly by enabling networks of actors, activities, and portfolios of projects. Most such organizations are (to various degrees) public. For instance, in the Dutch energy and mobility transitions, organizations were set up by public actors to bring private actors and their expertise together and arrange coherent interventions. Within such organizations, actors are expected to participate in their own capacity and not represent their organization’s interests [PS1, SPP4]. They are used for negotiating and finding common interests among actors [EIST11]. Such organizations can, however, be coopted by incumbent players, as shown in the Dutch [PS1, SPP4] and Norwegian cases [EIST15].

Second, coordination can also occur through informal networks, like interdepartmental communication among public actors. Informal mechanisms are widely present in historic transition case studies, particularly because innovations at early stages tend to have no formal institutional arrangements (Kemp et al, 1998). At early stages of a transition, actors have limited capacities for institutionalized channels of coordination, which explains why informal exchanges are more likely to occur. Coordination is particularly beneficial for innovation processes when it facilitates communication and knowledge sharing [SPP3, SPP5]. Yet, unless such informal collaboration becomes institutionalized, like through the establishment of an organization [EIST28, EIST31], it only has a marginal effect on a transition’s speed.

Both formal and informal coordination mechanisms facilitate dialogues between actors from different sectors or governance levels. They allow collaboration at interfaces that otherwise would not be connected, such as between users and producers, science and policy, or different economic sectors. They are also relevant for transitions that span multiple sectors. For instance, facilitating transitions towards carbon-free mobility calls for changes in infrastructure, which generally falls under the regulatory responsibility of various jurisdictions. This can be seen in vehicle electrification: regulating energy and transport under two different departments is the norm rather than the exception, thus demanding cross-ministerial dialogue.

Like all other policy interventions, policies directed at coordination face multiple difficulties. Here we focus on difficulties encountered by platform organizations (both informing and organizing transitions). Such organizations often rely on limited and temporary funding and tend to be bound to governmental terms [EIST28]. They are thus likely to eventually dissolve. Platform organizations are also likely to fail when they cannot generate shared expectations around a transition [TFSC38]. Additionally, multi-level governance settings (as those present in the EU) generate challenges in coordination. Incentives between different levels of government may be misaligned, as the experience of renewables at a national level in Europe shows [RP2]. Overall, since transitions increasingly span multiple domains, policy interventions supporting the coordination of multi-system transitions will become more important. Policy studies scholars can contribute to this area by offering approaches such as ‘policy regimes’ (Jochim and May 2010).

4. Conclusion

In this chapter, we introduced four theory areas of relevance for interventions for sustainability transitions – directionality, novelty creation, destabilization, and coordination – and synthesized empirical evidence from transition studies. The empirics allowed us to take stock of how and under what conditions interventions work. In addition, by linking the theoretical and empirical transitions literature with insights from the policy studies literature, we demonstrated ample complementarity that supports earlier calls for a stronger interdisciplinary exchange between the two fields (Kern and Rogge 2018, Kern et al. 2019).

We posit that there are several ways in which transition studies can leverage policy studies. Particularly, transition studies has not yet sufficiently engaged in discussions concerning the policy processes occurring as part of transitions. For this, policy studies offers an established canon of scholarship on how to open the black box of policymaking (Kern and Rogge 2018). This includes concepts on how to define, operationalize, and measure policy change, as well as frameworks and theories on how to explain this change over time. Since policy change is key for accelerating transitions, transition scholars are advised to better leverage these concepts, frameworks, and theories from policy studies. In addition, policy studies can help transition scholars more thoroughly analyze the politics of transitions. While there has been a political turn in transition studies, many transition frameworks continue to either downplay or overlook the role of politics. Policy studies can help address this omission by bringing upfront the contested and messy nature of political decision-making.

We recognize that there will be challenges in bridging both fields. Confusion and tension might arise, for instance, from different conceptualizations around how to capture and explain change. While policy studies has tended to employ variable-based approaches, whereby change is assessed vis-à-vis the effects of explanatory factors on dependent variables, transition studies often emphasizes complex causality, co-evolutionary processes, and the endogeneity of dependent and independent variables. Moreover, we predict that the normativity of transition studies could strike policy studies scholars as problematic. Many transition studies scholars tend to take a normative stand on how societal transformations ought to occur, which could be a point of controversy for policy scholars. We posit that if these and related challenges can be addressed constructively, the potential for interdisciplinary fertilization is significant.

In closing, we reiterate the urgent need to make policies and policy mixes more transformational, and to this end argue for stronger interdisciplinary dialogue between transition and policy studies. Ultimately, we hope this chapter will spark an increased interest in future research that bridges both fields and thereby provides sharper insights into how to deliberately accelerate sustainability transitions.

Andersson, J.; Hellsmark, H. & Sandén, B. (2021): The outcomes of directionality: Towards a morphology of sociotechnical systems. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 40, 08–131.

Avelino, F., & Wittmayer, J. M. (2016). Shifting power relations in sustainability transitions: A multi-actor perspective. Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning, 18(5), 628–649. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2015.1112259

Avelino, F., Grin, J., Pel, B., & Jhagroe, S. (2016). The politics of sustainability transitions. Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning, 18(5), 557–567. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2016.1216782

Avelino, F. (2017). Power in Sustainability Transitions: Analysing power and (dis)empowerment in transformative change towards sustainability. Environmental Policy and Governance, 27(6), 505–520. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1777

Baumgartner, F. & Jones, B. (1991): Agenda Dynamics and Policy Subsystems. The Journal of Politics 53 (4): 1044–1074. https://doi.org/10.2307/2131866

Baumgartner, F. & Jones, B. (1993): Agendas and Instability in American Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Berglund, O.; Dunlop, C. A.; Koebele, E. A.; Weible, C. M. (2022): Transformational change through Public Policy. Policy and Politics 50 (3): 302–322. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557322X16546739608413.

Derwort, P., Jager, N. & Newig, J. (2021): How to Explain Major Policy Change Towards Sustainability? Bringing Together the Multiple Streams Framework and the Multilevel Perspective on Socio‐Technical Transitions to Explore the German ‘Energiewende.’ Policy Studies Journal, May. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12428

Elstub, S., Selen Ercan, and Ricardo Fabrino Mendonça (2016): Editorial Introduction: The Fourth Generation of Deliberative Democracy. Critical Policy Studies 10 (2): 139–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2016.1175956.

Edmondson, D. L., Kern, F., & Rogge, K. S. (2019): The co-evolution of policy mixes and socio-technical systems: Towards a conceptual framework of policy mix feedback in sustainability transitions. Research Policy, 48(10), 103555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.03.010

Edmondson, D. L., Rogge, K. S., & Kern, F. (2020). Zero carbon homes in the UK? Analysing the co-evolution of policy mix and socio-technical system. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 35, 135–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2020.02.005

EEA. (2019). Sustainability transitions: policy and practice. EEA Report No. 09/2019 (Issue 09). https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/sustainability-transitions-policy-and-practice

European Commission (2021): A European Green Deal. Striving to be the first climate-neutral continent. Edited by European Commission. European Commission. Brussels. Available online at https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en#documents, checked on 9/27/2021.

Flanagan, K., Uyarra, E., & Laranja, M. (2011): Reconceptualising the `policy mix’ for innovation. Research Policy, 40(5), 702–713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.02.005.

Florini, A., & Markus Pauli (2018): Collaborative Governance for the Sustainable Development Goals. Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies 5 (3): 583–98. https://doi.org/10.1002/app5.252.

Fuenfschilling, L. & Truffer, B. (2016): The interplay of institutions, actors and technologies in socio-technical systems – An analysis of transformations in the Australian urban water sector. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 103, 298–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2015.11.023.

Garud, R.; & Gehman, J. (2012): Metatheoretical perspectives on sustainability journeys: Evolutionary, relational and durational. In Research Policy 41 (6), pp. 980–995. DOI: 10.1016/j.respol.2011.07.009.

Geels, F. (2004): From Sectoral Systems Of Innovation To Socio-Technical Systems: Insights About Dynamics And Change From Sociology And Institutional Theory. In Research Policy 33, pp. 897–920. DOI: 10.1016/j.respol.2004.01.015.

Geels, F. W. (2014). Regime Resistance against Low-Carbon Transitions: Introducing Poli-tics and Power into the Multi-Level Perspective. Theory, Culture & Society, 31(5), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276414531627

Geels, F. W., Turnheim, B., Asquith, M., Kern, F., & Kivimaa, P. (2019): Sustainability transitions: policy and practice. Brussels: European Environmental Agency. Available online: https://www. eea. europa. eu/publications/sustainability-transitions-policy-and-practice (accessed January 24, 2021).

Gomel, D., & Rogge, K. S. (2020). Mere deployment of renewables or industry formation, too? Exploring the role of advocacy communities for the Argentinean energy policy mix. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 36, 345–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2020.02.003

Grin, J., Rotmans, J., & Schot, J. (2010): Transitions to sustainable development: new directions in the study of long term transformative change. Routledge.

Hall, Peter (Ed.) (1989): The Political Power of Economic Ideas: Keynesianism across Nations. Princeton: Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691221380

Hall, P. (1993): Policy paradigms, social learning, and the state: the case of economic policymaking in Britain. Comparative Politics 25 (3): pp. 275–296. https://doi.org/10.2307/422246.

Hansmeier, H., Schiller, K., & Rogge, K. S. (2021): Towards methodological diversity in sustainability transitions research? Comparing recent developments (2016-2019) with the past (before 2016). Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 38, 169–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2021.01.001.

Henisz, W. J., & Bennet A. Zelner (2006): Interest Groups, Veto Points, and Electricity Infrastructure Deployment. International Organization 60 (01): 263–86. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818306060085.

Howlett, M., & Cashore, B. (2009): The Dependent Variable Problem in the Study of Policy Change: Understanding Policy Change as a Methodological Problem. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 11 (1): 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876980802648144.

Isoaho, K. & Markard, J. (2020): The Politics of Technology Decline: Discursive Struggles over Coal Phase‐Out in the UK. Review of Policy Research 37 (3): 342–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/ropr.12370.

Jacobsson, S. (2004): Transforming the energy sector: the evolution of technological systems in renewable energy technology. Ind Corp Change 13 (5), pp. 815–849. DOI: 10.1093/icc/dth032.

Jochim, A. E., & May, P. J. (2010): Beyond subsystems: Policy regimes and governance. Policy Studies Journal, 38(2), 303-327.

Johnstone, Phil, and Johan Schot. “Shocks, institutional change, and sustainability transitions.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 120.47 (2023): e2206226120.

Kanger, L., Schot, J., Sovacool, B. K., van der Vleuten, E., Ghosh, B., Keller, M., … & Steinmueller, W. E. (2021): Research frontiers for multi-system dynamics and deep transitions. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 41, 52-56.

Kanger, L.; Sovacool, B. K. & Noorkõiv, M. (2020): Six policy intervention points for sustainability transitions: A conceptual framework and a systematic literature review. Research Policy 49 (7), 104072. DOI: 10.1016/j.respol.2020.104072.

Kattel, R. & Mazzucato, M. (2018): Mission-oriented innovation policy and dynamic capabilities in the public sector. Ind Corp Change 27 (5), 787–801. DOI: 10.1093/icc/dty032.

Kemp, R. (1994). Technology and the transition to environmental sustainability: the problem of technological regime shifts. Futures, 26(10), 1023-1046.

Kemp, R.; Schot, J. & Hoogma, R. (1998): Regime shifts to sustainability through processes of niche formation: The approach of strategic niche management. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 10 (2), 175–198. DOI: 10.1080/09537329808524310.

Kern, F. & Howlett, M. (2009): Implementing transition management as policy reforms: a case study of the Dutch energy sector. Policy Sci 42 (4), 391–408. DOI: 10.1007/s11077-009-9099-x.

Kern, F. (2015). Engaging with the politics, agency and structures in the technological innova-tion systems approach. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 16, 67–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2015.07.001

Kern, F., & Rogge, K. S. (2018): Harnessing theories of the policy process for analysing the politics of sustainability transitions: A critical survey. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 27, 102–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2017.11.001.

Kern, F., Rogge, K. S., & Howlett, M. (2019). Policy mixes for sustainability transitions: New approaches and insights through bridging innovation and policy studies. Research Policy, 48(10). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2019.103832.

Kim, Serena Y., William L. Swann, Christopher M. Weible, Thomas Bolognesi, Rachel M. Krause, Angela Y.S. Park, Tian Tang, Kiernan Maletsky, and Richard C. Feiock. 2022. “Updating the Institutional Collective Action Framework.” Policy Studies Journal, 50 (1): 9–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12392.

Kivimaa, P. (2014): Government-affiliated intermediary organisations as actors in system-level transitions. In Research Policy 43 (8), pp. 1370–1380. DOI: 10.1016/j.respol.2014.02.007.

Kivimaa, P., Bergek, A., Matschoss, K., & Van Lente, H. (2020). Intermediaries in accelerating transitions: Introduction to the special issue. Environmental innovation and societal transitions, 36, 372-377.

Kivimaa, P.; Kangas, H.-L.; Lazarevic, D. (2017): Client-oriented evaluation of ‘creative destruction’ in policy mixes: Finnish policies on building energy efficiency transition. Energy Research & Social Science 33, 115–127. DOI: 10.1016/j.erss.2017.09.002.

Kivimaa, P. & Kern, F. (2016): Creative destruction or mere niche support? Innovation policy mixes for sustainability transitions. Research Policy 45 (1), 205–217. DOI: 10.1016/j.respol.2015.09.008.

Kivimaa, P., Hyysalo, S., Boon, W., Klerkx, L., Martiskainen, M., & Schot, J. (2019a): Passing the baton: How intermediaries advance sustainability transitions in different phases. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 31, 110-125

Kivimaa, P., Boon, W., Hyysalo, S., & Klerkx, L. (2019b). Towards a typology of intermediaries in sustainability transitions: A systematic review and a research agenda. Research Policy, 48(4), 1062–1075. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.10.006

Kivimaa, P., & Rogge, K.S. (2022): Interplay of policy experimentation and institutional change in sustainability transitions: The case of mobility as a service in Finland. Research Policy, 51, 104412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2021.104412.

Köhler, J.; Geels, Frank W.; Kern, F.; Markard, J.; Onsongo, E.; Wieczorek, A. et al. (2019): An agenda for sustainability transitions research: State of the art and future directions. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 31, 1–32. DOI: 10.1016/j.eist.2019.01.004.

Lennon, B., Dunphy, N. P., & Sanvicente, E. (2019). Community acceptability and the energy transition: A citizens’ perspective. Energy, Sustainability and Society, 9(1), 1-18.

Levy, B. & Pablo T Spiller (1994): The Institutional Foundations of Regulatory Commitment: A Comparative Analysis of Telecommunications Regulation. Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization, 10 (2): 201–46. https://www.jstor.org/stable/764966.

Lindblom, C. E. (1959): The Science of ‘Muddling Through.’ Public Administration Review, 19 (2): 79. https://doi.org/10.2307/973677.

Loorbach, D., Frantzeskaki, N., & Avelino, F. (2017). Sustainability transitions research: transforming science and practice for societal change. Annual review of environment and resources, 42, 599-626.

Markard, J.; Raven, R. & Truffer, B. (2012): Sustainability transitions: An emerging field of research and its prospects. Research Policy 41 (6), 955–967. DOI: 10.1016/j.respol.2012.02.013.

Markard, J., Rinscheid, A., & Widdel, L. (2021). Analyzing transitions through the lens of discourse networks: Coal phase-out in Germany. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 40, 315-331.

Markard, J., Suter, M., & Ingold, K. (2016): Socio-technical transitions and policy change – Advocacy coalitions in Swiss energy policy. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 18, 215–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2015.05.003

Meadowcroft, J. (2011). Engaging with the politics of sustainability transitions. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 1(1), 70–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2011.02.003

Meadowcroft, J., & Rosenbloom, D. (2023). Governing the net-zero transition: Strategy, policy, and politics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(47), e2207727120.

Meckling, J. (2015): Oppose, Support, or Hedge? Distributional Effects, Regulatory Pressure, and Business Strategy in Environmental Politics. Global Environmental Politics 15 (2): 19–37. https://doi.org/10.1162/GLEP_a_00296.

Meckling. J. & Nahm, J. (2019): The politics of technology bans: Industrial policy competition and green goals for the auto industry. Energy Policy, 126: 470–479. DOI/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.11.031.

Meckling, J., Sterner, T. & Wagner, G. (2010): Policy Sequencing toward Decarbonization. Nature Energy 2 (12): 918–22. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-017-0025-8.

Normann, H. E. (2015). The role of politics in sustainable transitions: The rise and decline of offshore wind in Norway. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 15, 180–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2014.11.002

Pahle, M., Dallas Burtraw, Christian Flachsland, Nina Kelsey, Eric Biber, Jonas Meckling, Ottmar Edenhofer, & Zysman, J. (2018): Sequencing to Ratchet up Climate Policy Stringency. Nature Climate Change 8 (10): 861–67. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0287-6.

Pawson, R.; Greenhalgh, T.; Harvey, G. & Walshe, K. (2005): Realist review—a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. Journal of health services research & policy, 10 Suppl 1, 21–34. DOI: 10.1258/1355819054308530.

Pierce, J. J., Holly L. Peterson, Michael D. Jones, Samantha P. Garrard, & Vu, T. (2017): There and Back Again: A Tale of the Advocacy Coalition Framework. Policy Studies Journal 45 (S1): S13–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12197.

Raven, R., Kern, F., Smith, A., Jacobsson, S., & Verhees, B. (2016). The politics of innova-tion spaces for low-carbon energy: Introduction to the special issue. Environmental Inno-vation and Societal Transitions, 18, 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2015.06.008

Reichardt, K., Negro, S. O., Rogge, K. S., & Hekkert, M. P. (2016): Analyzing interdependencies between policy mixes and technological innovation systems: The case of offshore wind in Germany. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 106, 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2016.01.029

Roberts, C., Geels, F. W., Lockwood, M., Newell, P., Schmitz, H., Turnheim, B., & Jordan, A. (2018): The politics of accelerating low-carbon transitions: Towards a new research agenda. Energy research & social science, 44, 304-311Rogge, K. S. (2019). Policy mixes for sustainable innovation: conceptual considerations and empirical insights. In Handbook of Sustainable Innovation (pp. 165–185). Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788112574.00016.

Rogge, K. S., & Dütschke, E. (2018): What makes them believe in the low-carbon energy transition? Exploring corporate perceptions of the credibility of climate policy mixes. Environmental Science & Policy, 87, 74–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2018.05.009.

Rogge, K. S., & Goedeking, N. (2024). Challenges in accelerating net-zero transitions: insights from transport electrification in Germany and California. Environmental Research Letters, 19(4), 044007. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ad2d8

Rogge, K. S., Pfluger, B., & Geels, F. W. (2020). Transformative policy mixes in socio-technical scenarios: The case of the low-carbon transition of the German electricity system (2010–2050). Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 151, 119259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.04.00

Rogge, K. S., & Schleich, J. (2018). Do policy mix characteristics matter for low-carbon inno-vation? A survey-based exploration of renewable power generation technologies in Ger-many. Research Policy, 47(9), 1639–1654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.05.011

Rogge, K.S., Kern, F., & Howlett, M. (2017): Conceptual and empirical advances in analysing policy mixes for energy transitions. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 33, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2017.09.025.

Rogge, K.S. & Johnstone, P. (2017): Exploring the role of phase-out policies for low-carbon energy transitions: The case of the German Energiewende. Energy Research & Social Science 33, 128–137. DOI: 10.1016/j.erss.2017.10.004.

Rogge, K. S.; Reichardt, K. (2016): Policy mixes for sustainability transitions: An extended concept and framework for analysis. Research Policy 45 (8), 1620–1635. DOI: 10.1016/j.respol.2016.04.004.

Rosenbloom, D., 2020. Engaging with multi-system interactions in sustainability transitions: A comment on the transitions research agenda. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transitions 34, 336–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2019.10.003.

Rotmans, J.; Kemp, R. & van Asselt, M. (2001): More evolution than revolution: transition management in public policy. Foresight 3 (1), 15–31. DOI: 10.1108/14636680110803003.

Ruggiero, S., Martiskainen, M., & Onkila, T. (2018). Understanding the scaling-up of community energy niches through strategic niche management theory: Insights from Finland. Journal of cleaner production, 170, 581-590.

Sabatier, P. A., & Weible, C. M. (2019). The advocacy coalition framework: Innovations and clarifications. In Theories of the Policy Process, Second Edition (pp. 189-220). Routledge.

Salas Gironés, E., van Est, R., & Verbong, G. (2019): Transforming mobility: The Dutch smart mobility policy as an example of a transformative STI policy. Science and Public Policy, 46(6), 820-833.

Schmid, N., Sewerin, S., & Schmidt, T.S. (2020): Explaining Advocacy Coalition Change with Policy Feedback. Policy Studies Journal 48 (4): 1109–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12365.

Schot, J.; Hoogma, R.; Elzen, B. (1994): Strategies for shifting technological systems. In Futures 26 (10), 1060–1076. DOI: 10.1016/0016-3287(94)90073-6.

Schot, J. & Steinmueller, W. E. (2018): Three frames for innovation policy: R&D, systems of innovation and transformative change. Research Policy 47 (9), 1554–1567. DOI: 10.1016/j.respol.2018.08.011.

Scott, T.A., & Craig W. Thomas (2017): Unpacking the Collaborative Toolbox: Why and When Do Public Managers Choose Collaborative Governance Strategies? Policy Studies Journal, 45 (1): 191–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12162.

Sengers, F.; Wieczorek, A. J.; Raven, R. (2019): Experimenting for sustainability transitions: A systematic literature review. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 145, 153–164. DOI: 10.1016/j.techfore.2016.08.031.

Smith, A. & Raven, R. (2012): What is protective space? Reconsidering niches in transitions to sustainability. Research Policy 41 (6), 1025–1036. DOI: 10.1016/j.respol.2011.12.012.

Song, Q., Rogge, K., & Ely, A. (2023). Mapping the governing entities and their interactions in designing policy mixes for sustainability transitions: The case of electric vehicles in China. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 46, 100691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2023.100691

Trachtman, S. (2021): Policy Feedback and Interdependence in American Federalism: Evidence from Rooftop Solar Politics. Perspectives on Politics, April, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1017/S153759272100092X.

Unruh, G. C. (2000): Understanding carbon lock-in. Energy Policy 28 (12), 817–830. DOI: 10.1016/S0301-4215(00)00070-7.

Voss, J. P., Bauknecht, D., & Kemp, R. (Eds.). (2006). Reflexive governance for sustainable development. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Weber, K. M. & Rohracher, H. (2012): Legitimizing research, technology and innovation policies for transformative change. Research Policy 41 (6), 1037–1047. DOI: 10.1016/j.respol.2011.10.015.

Weible, C.M.; Sabatier, P.A.; Jenkins-Smith, H.C.; Nohrstedt, D.; Adam Douglas Henry & deLeon, P. (2011): A Quarter Century of the Advocacy Coalition Framework: An Introduction to the Special Issue. Policy Studies Journal 39 (3): 349–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2011.00412.x.

Zahariadis, N. (2019). The multiple streams framework: Structure, limitations, prospects. In Theories of the policy process, second edition (pp. 65-92). Routledge.

Zolfagharian, M.; Walrave, B.; Raven, R.; Romme, A.G.L. (2019): Studying transitions: Past, present, and future. Research Policy 48 (9), 103788. DOI: 10.1016/j.respol.2019.04.012.