Introduction

Intermediaries have received research attention in the field of innovation management since the 1990s (e.g., Bessant and Rush, 1995). However, it is only in the last decade that intermediaries have begun to receive scholarly attention in the sustainability transitions literature (Kivimaa et al., 2019a). Howells (2006) defines an innovation intermediary as “an organization or body that acts as an agent or broker in any aspect of the innovation process between two or more parties” (p.720). Intermediaries have been identified as key catalysts that can facilitate sustainability transitions by connecting actors – both new entrants and incumbents – and their related activities, skills, and resources to create momentum for change and disrupt unsustainable socio-technical systems (Kivimaa et al., 2019a). Thus, previous studies on intermediaries in sustainability transitions have among others focused on defining what intermediaries are, the activities they undertake, their different types, interactions between them, and their potential influence on transition processes (Kanda et al., 2020).

In the sustainability transitions literature, a variety of private, public, and non-profit entities have been studied as intermediaries. These include for example cities, technology transfer offices, internet platforms, architects, clusters, innovation agencies, ports, charities, and industry associations. These entities have different characteristics e.g., ownership and governance structure, source of funding, mandate, scope of impact and capacity to catalyse change (Bjerkan et al., 2021; Mignon and Kanda, 2018). Some intermediaries seek neutrality and carry out their activities without altering the knowledge or goods being transferred, a notion particularly prominent in the innovation management literature (Klerkx and Leeuwis, 2009). The position of being impartial and neutral to suppliers, network partners, or preferred development strategies is particularly important in innovation management for intermediaries to be considered trustworthy by third parties. Other intermediary types work actively to shape the entities being transferred. Furthermore, some intermediaries have a normative orientation and champion the course of certain technologies and actors, a discourse which has emerged strongly in the transitions literature given the urgency and limited time to facilitate sustainability transitions (Kivimaa, 2014).

Intermediaries can be a specific actor category, either an individual or an organization. They can also be group of individuals or organizations with a complex set of interrelationships (Hyysalo et al., 2022) essentially forming an ecology of intermediation (Stewart and Hyysalo, 2008). Within an ecology of intermediaries, entities have different remits (e.g., scope of responsibility, authority, or tasks), opinions, visions, competencies and operational mechanisms. Thus, they cooperate and sometimes compete to facilitate transition processes by going in-between other actors and their related activities, skills and resources (Soberón et al., 2022). While intermediaries can be strategically established with a given mandate, the literature suggests most entities evolve to undertake intermediary activities during a transition. Other actors might engage in intermediary activities without acknowledging it. Intermediaries range from short-term, project-based entities which can be terminated after their mandate period, to more long-term and established entities that take on new roles as the transition evolves. As a result, intermediaries span a spectrum from formal, self-recognised and defined forms to informal and emergent forms of intermediation (Kivimaa et al., 2019a).

The concept of intermediaries can also be related to actor roles and agency (see Chapter 17) in the broader sustainability transitions literature (Hodson and Marvin, 2010; Köhler et al., 2019; Rohracher, 2009). In this regard, studies using notions such as “middle actors” (Parag and Janda, 2014), “hybrid actors” (Elzen et al., 2012), “boundary spanners” (Smink et al., 2015), “user assemblages” (Nielsen, 2016), “interaction arenas” (Hyysalo and Usenyuk, 2015), “orchestrators” (de Vasconcelos Gomes and da Silva Barros, 2022) and “system entanglers” (Löhr and Chlebna, 2023) have also analysed intermediary-like activities sometimes without explicitly mentioning intermediaries.

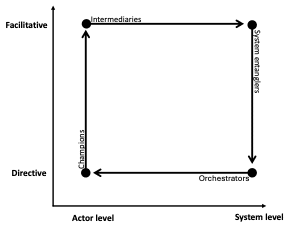

The concept of an intermediary is essentially contested. The literature lacks consensus regarding where intermediation begins and ends, when an interaction between actors in general becomes intermediation and how to define it (Kivimaa et al., 2019a). To differentiate intermediaries from other actors like middle actors, hybrid actors, orchestrators, and boundary spanners which undertake intermediary-like activities, there is a growing consensus in the literature that intermediaries should be defined by what they do (i.e., intermediation), rather than by who they are (Bergek, 2020). Thus, Kanda et al., (2020 p. 453) argue that intermediaries can be identified and differentiated from other intermediary-like actors based on a combination of three criteria: (i) their position in-between two or more parties, (ii) the activities they undertake, and (iii) the scope of impact of their activities. In contrast to other actors, intermediaries have generally a facilitative role in a transition by going in-between two or more actors enabling, supporting and assisting other actors in achieving their goals (Soberón et al., 2022). On the contrary, other intermediary-like actors such as orchestrators can have more directive roles which involves leading, managing and making decisions to guide the actions of other actors (de Vasconcelos Gomes and da Silva Barros, 2022). System entanglers on the other hand connect different socio-technical systems (Löhr and Chlebna, 2023) while champions are individuals who actively and enthusiastically promote innovations to overcome the social and political pressures imposed by an organization and convert them to its advantage (Howell et al., 2005).

The literature on intermediaries in sustainability transitions has expanded rapidly. Thus, this chapter seeks to provide the reader with a brief overview of intermediaries and intermediation in sustainability transitions (Section 1). This overview is then followed by a brief historical account of the development of the concept (Section 2). Thereafter, we provide some empirical examples of intermediaries in Section 3, followed by a problematization of the literature specifically with regards to its lack of a clearly articulated theory on why intermediaries exist in transition processes (Section 4). Finally, we identify future research opportunities in Section 5.

2. Foundations of the intermediary concept in transitions

The literature on intermediaries in sustainability transitions builds upon four earlier streams of literature – technological regimes, techno-economic networks, systems of innovations, and innovation management (Kivimaa et al., 2019a) .

The literature on technological regimes by scholars such as Nelson and Winter inspired the work of Geels and Deuten (2006) on the dedicated aggregation activities of intermediary actors to facilitate knowledge flows between local and global levels for niche development. This later inspired other contributions on intermediary activities in niche development from scholars such as Hargreaves and colleagues (Hargreaves et al., 2013) who analysed the role of community energy projects as intermediaries in niche development. A second stream of intermediary literature (e.g., Hodson and Marvin, 2010) took inspiration from techno-economic networks with contributions from Callon and Latour to make empirical contributions on the activities of intermediaries in shaping urban infrastructure with a specific interest in the governance of socio-technical networks.

Starting with the systems of innovation literature with key contributions from Lundvall, Nelson and Edquist, van Lente et al., (2003) introduced the concept of systemic intermediaries which operate at the system or network level. Their contribution inspired several other contributions on systemic intermediaries in the agricultural and renewable energy transition context (e.g., Kivimaa, 2014; Klerkx and Leeuwis, 2009). Finally, the literature on intermediaries in innovation management in particular the work of Howells in 2006 had substantial influence on the discourse on intermediaries in sustainability transitions. This literature inspired several contributions on the roles of intermediaries in system level transitions (e.g., Kivimaa, 2014).

More recently, the intermediary concept has also been used in relation to the core theoretical frameworks in sustainability transitions such as the multi-level perspective, technological innovation systems, strategic niche management, and transitions management. In the multi-level perspective, it is argued that intermediary actors can aggregate and transform knowledge and experiences from local niches to a shared global development trajectory (Geels and Deuten, 2006). In this context, intermediaries circulate, aggregate lessons and transfer knowledge across local experiments, potentially contributing to the upscaling of experiments beyond niches and challenging the status quo (Matschoss and Heiskanen, 2017). Intermediaries fulfil brokerage roles in technological innovation systems (see Chapter 3) by addressing the flow of knowledge and the formation of networks to tackle system failures related to the in-effective collaborations and resource mobilization which stifle innovation (Célia and Marie-Benoît, 2023; Kanda et al., 2019). Intermediaries can contribute to several of the niche internal processes in strategic niche management such as the articulation of expectations and visions (e.g., articulation of needs, expectations, and requirements; acceleration of the application and commercialisation of new technologies), building of social networks (e.g., creating and facilitation of new networks; configuring and aligning interests), and learning and exploration processes (e.g., knowledge gathering, processing, generation and combination; technology assessment and evaluation; prototyping and piloting) (Kivimaa, 2014).

The concept of intermediaries is often used in relation to actor roles and agency in sustainability transitions. Transition processes require the governance of interactions between multiple actors, networks, and institutions which can exceed the capabilities of any single actor. In this regard, intermediaries are needed to go in-between diverse groups of actors with the ambition to catalyse multi-actors’ interactions for systemic change. The contribution of van Lente et al., (2003), on systemic intermediaries largely kicked-off the interest in intermediary actors among transition scholars. Following this, a dominant focus in the sustainability transitions literature has been on the activities intermediaries undertake in different transition processes. The activities of intermediaries also change during the course of a transition in a co-evolutionary manner with the intermediary characteristics and context (Kivimaa et al., 2019b). Besides sustainability transitions, the concept of intermediaries has been used in other related literature. In eco-innovation, intermediaries perform activities to validate environmental benefits associated with eco-innovations and to internalize positive externalities in their development and diffusion (Kanda et al., 2018). Intermediaries influence the rate of innovation diffusion by gathering and disseminating information, and mobilizing and distributing resources that facilitate the adoption of innovations between suppliers and adopters (Lichtenthaler, 2013).

Moving on, several typologies of intermediaries have been proposed in the literature. For example, van Lente et al. (2003 p.257), adopting a systems approach, distinguished between three types of intermediaries – hard, soft, and systemic – based on their activities in innovation systems. Klerkx and Leeuwis (2009) made a similar contribution of seven types of intermediaries empirically operating in the Dutch agricultural innovation systems based on their activities. More recently, Kivimaa et al. (2019a p. 1068) introduced the concept of transition intermediaries. They define transition intermediaries as actors or platforms that facilitate transitions by connecting different groups of actors and their skills and resources. Transition intermediaries also bring together different ideas and technologies to create new collaborations and challenge un-sustainable socio-technical systems. Kivimaa et al (2019) present five types of transition intermediaries based on their emergence, neutrality, intermediation goals, and their level of action. These characteristics essentially capture the level (i.e., actor vs. system level) of operation of intermediaries and their ambitions. The typology of transition intermediaries proposed by Kivimaa et al (2019) are:

- A systemic intermediary – operating on the niche, regime, landscape levels with an explicit transition agenda for whole system transformation. Systemic intermediaries operate on the system level between multiple actors and are typically established to intermediate.

- A regime-based transition intermediary – associated with the prevailing regime but with a specific ambition to promote transition. Thus regime-based intermediaries interact with a range of niches or the whole system.

- A niche intermediary – working to experiment and advance the activities and development of a particular niche. In doing so, niche intermediaries strive to influence the prevailing socio-technical system for the niche’s benefit.

- A process intermediary – facilitates change in a niche project without an explicit system transformation agenda of their own. Often, they support context-specific (e.g., project based or spatially located) agendas and priorities set by other actors to facilitate change.

- A user intermediary – connects users to new technology and communicates user preferences to technology developers. User intermediaries also translate new niche technologies to users, altogether qualifying the value of technology offers available between users, developers and regime actors.

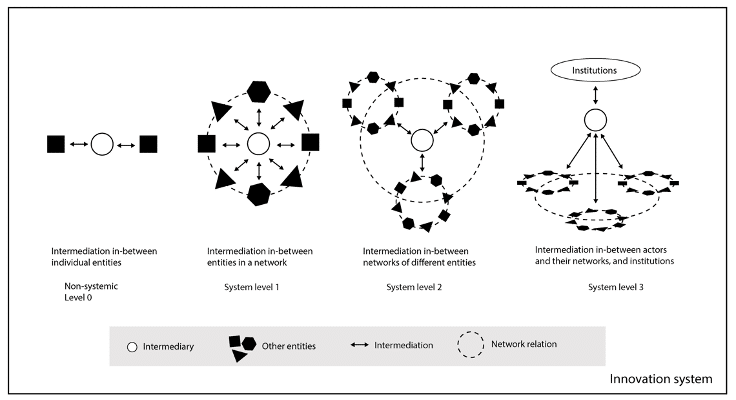

In extending the discourse on the typology of transition intermediaries, a particular gap remained in the literature on how to conceptualize and demonstrate the contribution of intermediaries beyond the actor-level (often in bilateral one-to-one intermediation) to the broader system (often including multiple actors, their networks and related institutions). Furthermore, the strategic activities of intermediaries as operating across multiple system-levels had received limited scholarly attention. Kanda et al., (2020) defined three systemic levels of aggregation (see Figure 1 below) within which intermediation occurs. These are: (i) system level 1 – in-between entities in a network, (ii) system level 2 – in-between networks of entities and (iii) system level 3 – in-between actors, networks, and institutions. This classification was based on: (i) the intermediation activities, (ii) in-between which third parties it occurs, and (iii) the scope of intermediation impact.

A non-systemic level is included as a benchmark and is characterized by “one-to-one” interactions. Intermediaries at this level are typically private organizations, such as consultants, who assist their clients in achieving innovation objectives for a fee. This level of intermediation is not considered a systemic since it does not explicitly seek to generate intermediation benefits beyond the third parties. However, intermediaries at this level can learn and build competence from different cases, which can be applied in their subsequent intermediation activities.

In system level 1, intermediation occurs between different entities within a network, such as a technology cluster or a niche coalition. The intermediaries facilitate learning and knowledge transfer between the network’s members through various physical arenas such as conferences, seminars, and workshops. The intermediary helps to build a brand and legitimacy for the network’s activities and its members work towards a common interest. In system level 2, intermediation occurs between networks of different entities, where the intermediary facilitates interactions and collaborations in a “many-to-many-to-many” form also referred to as a network of networks. These networks can represent different technological fields, such as solar or wind power networks, where members come together to facilitate low-carbon energy transitions. Intermediaries may create interaction spaces, disseminate information, and provide brokerage support to address market or innovation system failures that result in sub-optimal connectivity between different actors and their networks.

In system level 3, intermediation activities go beyond the interactions between different types of networks to include interactions between actors, networks, and relevant institutions. Institutions can be either informal (e.g., norms, values, and culture) or formal (e.g., laws, regulation, and technical standards) that shape the activities and decisions of actors. When intermediaries see an opportunity to realize interests, they highly value, they engage in different types of purposive and strategic actions to create, maintain, or disrupt institutions sometimes acting as institutional entrepreneurs (DiMaggio, 1988). Overall, intermediation at system level 3 involves shaping the institutional environment to enable the achievement of collective interests across different actor-networks.

Finally, while intermediaries are more likely to be conceptualized and profiled as one type (i.e., systemic, regime-based, niche, process, or user intermediary) rather than portraying characteristics of several, in practice, intermediaries are strategic actors who can change their profile and operate on multiple system levels undertaking different activities to facilitate transitions. Altogether, this contribution from Kanda et al., 2020 challenged the notion that intermediaries are homogenous entities (e.g., with regards to their roles and activities) and operate at a particular system level. The contribution opened several opportunities for further studies on the strategic actions of intermediaries which move across system levels leading to cooperation and competition, role adaptation, differentiation, and power struggles among ecologies of intermediaries. This revealed a darker side of intermediaries beyond their facilitate role which at worse could even hinder transitions. The contribution also laid an essential foundation to explore the question about intermediary impact on system levels i.e., specifically by analysing how intermediary activities contribute to overall structure and functions in the system levels identified during a transition.

3. Empirical examples of intermediary activities

In table 1 below, we provide illustrative examples of the activities of the different types of transitions intermediaries in relation to different system levels of intermediation. The activities mainly come from the activities of intermediaries identified in Kivimaa et al., (2019a) and Kanda et al., (2020). These activities are then placed on different system levels depending on the entities in-between which they take place and the scope of their potential impact i.e., within a network, between different networks, towards institutions or a fee-paying client.

Table 1: Transition intermediary types and their activities across different system levels (Source: authors based on Kivimaa et al. 2019a and Kanda et al., 2020).

| System levels within which intermediaries operate | ||||

| Transition intermediaries | Non-systemic intermediation (Level 0) | Intermediation in-between actors in a network (System level 1) | Intermediation in-between networks of different entities (System level 2) | Intermediation in between actors and their networks, and institutions (System level 3) |

| Systemic intermediaries | N/A | Mobilize government, knowledge institutions, other societal organizations, and companies to innovate for sustainable development – Innovation Network Rural Areas and Agricultural Systems in the Netherlands | Creating a forum to mobilize actors from different renewable energy niches to develop innovations for sustainable development – The Finnish Clean Energy Association | Aggregating and aligning the views of multiple renewable energy networks to lobby for policy change beyond the reach of the individual networks – The Finnish Clean Energy Association |

| Regime-based transition intermediary | Rarely | Facilitating low-carbon transitions through diverse funding streams, developing capacity for behavioural change work, supporting businesses, and developed critical infrastructure – The Greater Manchester Climate Change Agency | Facilitating collaboration between bioenergy advisors, heat entrepreneurs, and renewable energy associations for low-carbon energy transitions – Motiva, a Finnish government-owned energy and resource efficiency company | Translate new forms of regulation into practise and make sense of complex and changing policy environments for innovators and entrepreneurs – Motiva, a Finnish government-owned energy and resource efficiency company |

| Niche intermediary | The agency offers SMEs customized support for improving energy efficiency in production processes through information, technical consulting, education, networking, and financial assistance – The Energy Agency, NRW, Germany | Coordinating community energy projects in protected spaces, promoting learning activities and articulation of expectations –Grassroots intermediaries UK | The agency facilitates networking between companies and research institutions for renewable energy technologies, accelerating innovation and commercialization, including export – The Energy Agency, NRW, Germany | Developing a voice, facilitating vision, and formalizing the wave energy niche – WAVEC, a Portuguese wave energy association established in 2003, and the European Ocean Energy Association established in 2006 |

| Process intermediary | Process intermediaries facilitate projects within a niche or transition processes, collaborating with project managers and champions. They handle day-to-day management responsibilities – e.g., Project manager | Employed to facilitate the realization of a specific project through arenas of networking and information exchange e.g., intermediaries, such as eco open homes events or sustainability integrators in building projects, can facilitate progress towards zero-carbon buildings – e.g., Sustainability manager | Process intermediaries enable the realization of visions and expectations by turning them into actions, facilitate vertical and horizontal cooperation and handle external relations of the projects – e.g., Architects | They often lack an explicit institutional change agenda |

| User intermediary | Intermediary role in translating building energy efficiency requirements to their clients – e.g., Architects | Creating knowledge-sharing networks that can grow into significant information infrastructures through virtual communities, potentially enhancing the size and stability of the accelerating niche – e.g., internet discussion forums for electric vehicles | Rarely | They often lack an explicit institutional change agenda |

Essentially, Table 1 depicts the potential scope of impact of different transition intermediary types and their related activities. Some intermediary types e.g., systemic intermediaries dominantly operate at higher system levels in-between actors, their networks and institutions. On the other end of the spectrum, the activities of user intermediaries are dominated by bilateral one-to-one intermediation activities in-between third parties. Thus, the potential impact of different intermediary activities can be system-wide generating benefits for numerous actors and their networks or limited to the third parties in-between which the intermediation takes places. Due to the potential spillover of benefits from higher system level intermediation, intermediaries operating at such levels (e.g., systemic intermediaries) are often publicly affiliated through funding, ownership, and mandate to generate public good that can facilitate a transition beneficial for many actors (e.g., Sitra and Motiva in Finland; Vinnova in Sweden). On the other hand, in bilateral one-to-one intermediation as often practiced by user intermediaries, one of the parties could be a paying client and can seek to capture all the benefits from the intermediation process limiting the (positive) system-wide spillovers. Nonetheless, intermediaries accumulate benefits (e.g., knowledge, legitimacy) which can be transferred to other system levels. Similarly, the entities in-between which intermediaries operate can benefit differently (even in the same network) from the intermediation activities which can be at the expense of competing niches not part of the network.

4. Theoretical problematization: why do intermediaries exist in transitions?

A research gap we dedicate particular attention to is the lack of a clearly articulated theory on why intermediaries exist in transition processes. Research shows that intermediaries have important facilitating roles in transitions. Still, there is no congruent theory which explains why intermediaries exist in transition processes. Considering the eclectic nature of transition studies as a research field, this is hardly surprising. Theoretical explanations are important since they provide justifications for the establishment of intermediaries. In search of answers to the question why intermediaries exist in transitions, we return to the definition of transitions as major changes of socio-technical systems (Köhler et al., 2019). Such systemic changes will likely display gaps, glitches and tensions between different actors, their individual strategies, and the activities they engage in. By bridging organizational boundaries, intermediaries can help fil out such gaps and glitches, and work to resolve tensions. The characteristics of boundaries are central topics in many theories on organization. Santos and Eisenhardt (2005) present four different conceptions of organizational boundaries with different theoretical foundations. These conceptions are useful to explain why intermediary organizations exist in transition processes.

The first conception, which is denoted efficiency is based on institutional economics, considering the organization a legal entity with a prime motive to minimize costs and maximise return on investments. Derived from the seminal paper by Coase (1937) on the nature of business firms, transaction costs are central in the reasoning. Coase built his argumentation on a dichotomy between markets and firms, arguing that firms exist when the costs of market-based transactions are higher than the costs of hierarchical control. In their systematic review of literature on intermediaries, Kivimaa et al., (2019a) argue that transaction costs is a common explanation for the existence of intermediaries in innovation studies and science and technology studies. In cases when the costs of market-based transactions are high, intermediaries can absorb risks and reduce transaction costs for the organizations involved. The intermediary thus acts as a broker to facilitate exchanges in cases when neither market-based transactions, nor strict hierarchical control are feasible options.

The second conception is denoted competence. Building on evolutionary economics (Nelson, 1985) and the resource-based view of the firm (Penrose and Penrose, 2009) this conception posit that organizations are bundles of resources that co-evolve with the environments that they operate in. The competence conception is congruent with transition research that shows how intermediaries help facilitating knowledge flows between organizations (Geels and Deuten, 2006). To facilitate such flows, intermediaries aggregate local experiences into knowledge that is accessible for a variety of actors. Being more dynamic than the efficiency conception, the competence conception draws attention to the strategic development of resource portfolios that can result in long-term competitive advantages. Being located in-between different organizations and their resources, intermediaries undertake important activities to mobilize resources to facilitate synergies that can support transition processes.

The third conception power further elaborates on the competitive strategies of individual actors. Following theories on industrial organization and resource dependence (Porter, 1990), the conception is based on the assumption that organizations strive to reduce their exposure to uncertainties due to external contingencies. Important strategies for such uncertainty reduction are to gain influence and control through alliances and network engagement, and though lobbying activities. As transitions involve a large variety of actors who strive to maximise their own influence and control, intermediaries are often needed to establish trust between different parties. Moreover, studies have shown how intermediaries are instrumental to influence regulatory processes in favour of transitions (Hyysalo et al., 2018). Gathering a variety of actors, intermediaries can gain a stronger influence than the actors do individually.

The final conception identity conceptualises organizations as social entities for sensemaking (Weick, 1995). The conception is based on literature on organizational behaviour and managerial cognition, which draw attention to the cognitive frames that shape interpretations and actions. Once accepted, such frames constitute a strong mechanism for coordination. Transition studies have often referred to cognitive frames and routines as explanations to the persistence of regimes. However, studies also show that cognitive processes are important for niche development. These studies suggest that socially constructed narratives can enrol support for transitions and help shaping markets (Ottosson et al., 2019). Through their socio-political work, intermediaries can assist the construction of narratives that link actors together.

| Conception of boundaries | Theoretical foundation | Functions of intermediary | Role of intermediary |

| Efficiency | Institutional economics | Facilitate exchanges by absorbing risks and reducing transaction costs | Broker |

| Competence | Evolutionary economics, Resource-based view | Enable synergies through knowledge transfer and aggregation | Translator |

| Power | Industrial organization, resource dependence theory | Establishing trust by arbitrating and negotiating | Mediator |

| Identity | Organizational behaviour, managerial cognition | Sense-making through the construction of narratives and visions | Sense-maker |

In summary, the four conceptions provide complementary answers to the question why intermediaries exist in transitions. Table 2 summarises the conceptions in terms of their theoretical foundations, as well as the related functions and roles of the intermediary. For intermediaries, activities refer to tangible, specific actions, or tasks they undertake to facilitate sustainability transitions while roles refer to the positions or responsibilities intermediaries hold such as brokers, translators, and mediators. Functions on the other hand refers to the broad and strategic areas of responsibility that intermediaries have. In the efficiency conception the intermediary acts as a broker to absorb risks and reduce transactions costs. This conception is useful when analysing intermediation between sellers and buyers, or more broadly stated: between a supply-side and a demand side actors. However, transitions processes tend to involve a multitude of actors and modes of interaction. In this respect, the competence conception may be more useful, describing the intermediary as a translator that enable synergies and interorganizational knowledge flows. Still the competence conception tends to underplay critical issues of conflict and contestation. By contrast, these issues are central for the power conception. This conception describes the intermediary as a mediator, whose central function is to establish trust through arbitration and negotiation in inter-organizational networks. The conception is also useful to explain the role of intermediaries in advocacy activities and lobbying. While the power conception is based on the premise of disparate interests among actors, the identity conception adds another dimension by claiming that transition processes will depend on a shared meaning and a common purpose among a multitude of actors. To help building such a purpose, intermediaries take the role of a sense-maker, engaging of actors in the construction of narratives and visions to make sense of the transition. Adopting and further developing this conceptualization will enable to explore questions such as power relations, the politics at play, the normative positioning of intermediary actors, and the battle between different intermediaries (Kivimaa et al., 2019a).

5. Emerging research and further needs

Although the facilitating role of intermediaries in sustainability transitions is widely recognized, a critical analysis of the literature reveals diverse meanings and approaches to the concept. Thus, the concept of intermediaries remains essentially contested. It has multiple and diverse meanings, and its proper use may not be definitively settled by reference to empirical evidence, logical demonstration, or formal criteria alone. Thus, we expect persistent disagreement among scholars on the meaning, scope, and normative implications of the concept of intermediaries which cannot be easily resolved. Furthermore, in the literature, an extensive number of activities are attributed to intermediaries which raises questions about the credibility and capacity of intermediaries to undertake such numerous tasks effectively. Thus, there is a need to position intermediaries in transitions in relation to other actors and their agency in transitions, delineating which activities can (or cannot) be undertaken by intermediaries and their interplay with the activities of other transition actors such as orchestrators, system entanglers, and champions (see Figure 2).

Second, the impact of intermediaries on the actor level (e.g., projects and firms) are relatively tangible and easier to capture. However, it is particularly challenging how the impact of intermediaries is aggregated unto the system level. This stems from the difficulty in attributing cause and effects in long term transition processes where multiple actors (e.g., intermediaries, orchestrators, champions, system entanglers), processes and influences are involved. Attempts have been made to conceptually link the actor level activities to system level impact via different theoretical perspectives such as the Technological Innovation Systems (TIS) (e.g., Kanda et al., 2019), and Strategic Niche Management (SNM) (e.g., Kanda et al., 2022; Kivimaa, 2014). These previous attempts essentially map the tangible and specific actions, or tasks intermediaries undertake to facilitate transitions onto the TIS functions or SNM processes as a proxy for system level impact. However, for system level impact of intermediaries to be explored effectively, there is a need for further conceptualization of the system levels as started in (Kanda et al., 2020), robust empirical evidence and in particular new methodological developments on causality and explanation in the broader transitions literature (see e.g., Geels, 2022).

Third, the scholarly discourse needs to move beyond the dominant focus on the role of intermediaries in facilitating niche innovations and to explore their role in other contexts such as in the destabilization of regimes. An important question in this respect is to investigate how intermediaries can actively work to destabilize unsustainable socio-technical systems and by doing so create windows of opportunities for niche innovations. This is particularly important given the urgency of sustainability transitions and the need for transformative intermediation. This will also require investigating how intermediaries adapt to different contexts and tasks, as well as examining the different types of intermediaries and capabilities needed to destabilize regimes. Intermediation with the purpose to destabilizing regimes might also reveal the strategic struggles of intermediaries to make an impact giving a more nuanced understanding of intermediation in practise.

The literature has also been very positive towards intermediaries as facilitating transitions. However, future research could explore the role of power struggles and conflicts in the work of intermediaries, as their contribution to sustainability transitions can be contested. Research in this area could examine how intermediaries negotiate conflicting interests, manage power dynamics, and navigate complex stakeholder environments. This research trajectory is important to provide more nuance to the idealistic picture of intermediaries presented in the literature as always seeking to facilitate transitions. Already on the actor level, there is empirical evidence to the effect that intermediaries sometimes prioritize their own survival and interests over broader system goals (Kant and Kanda, 2019). Thus, contributions on the complexity of intermediation and dilemmas will be welcome.

Furthermore, studies of intermediaries acting in isolation dominate the literature. However, as innovations diffuse from niches into mainstream markets, multiple transitions pathways emerge, accelerate and interact as argued in recent scholarship on multi-system transitions (Andersen and Geels, 2023). Thus, intermediation is no longer an activity undertaken by single actors in isolation but instead, ecologies of intermediation are needed in which intermediaries with different mandates, competencies, goals and interests, operate at different system levels scale and time (Barrie and Kanda, 2020; Hyysalo et al., 2022). In such ecologies of intermediaries, entities collaborate; but also compete for dominance, may struggle to fit the context, and can lack relevant capabilities (Soberón et al., 2022). This demand delving into conflicts that can arise among intermediaries and how to address them. Thus, research needs to explore the dynamics in ecologies of intermediation, including their emergence, development, and governance mechanisms. This provides an opportunity to explore the similarities and differences between intermediaries and other transition actors e.g., system entanglers, orchestrators and champions who might emerge equally important in multi-system transitions (see Figure 2).

Furthermore, in multi-system transitions, intermediation can bridge actors from different socio-technical systems and create spaces for them to act (e.g., co-develop new knowledge and technology, align strategy and share resources) (Löhr & Chlebna, 2023). There is a need for new insights about how intermediaries can shape multi-system transitions, e.g. by breaking couplings between unsustainable systems and bridging sustainable systems (Kanger et al., 2021), visioning new cross-system configurations (Löhr & Chlebna, 2023), enabling learning and facilitating the flow of resources across multiple systems for example in cross sectoral transitions such as the circular economy (cf. Kanda et al., 2021). Essentially, multi-system transitions demands an ecology of intermediaries (Barrie & Kanda, 2020) particularly active at the intersection between regimes and niches (Geels & Deuten, 2006; Klerkx & Leeuwis, 2008). Thus, it will be naive to expect only facilitative intermediaries as part of transitions. There are intermediaries with an open (or hidden) agenda to defend the existing regime e.g. lobby organizations. Research about these types of obstructive intermediaries is crucial, to counteract their active work to hinder and create barriers to transitions.

In sustainability transitions, various actors play crucial roles based on their scope and approach of action (see Figure 2). Intermediaries, often with a starting position on the local actor level are facilitative and bridge actors and their related activities, skills, resources to create momentum for systemic change (Kivimaa et al., 2014). System entanglers, connect socio-technical systems and are facilitative, working across systems to align and integrate efforts, facilitating coherence among diverse actors (Hodson & Marvin, 2010). Finally, Champions can be directive at the actor level, spearhead initiatives and build networks, mobilizing support and fostering collaboration across sectors. Orchestrators are systemic and more directive, making strategic decisions to guide multi-actor processes. Essentially, the primary difference between facilitative and directive actors lies in their mechanism of operation. Facilitative roles focus on enabling others to act, while directive roles focus on leading and managing actions of others. Both are crucial for successful sustainability transitions operating at complementary system and actor levels to drive change. However, transition actors are strategic actors and can change their attributes across space and time to maintain relevance and longevity.

Thus, positioning intermediary actors in relation to other actors in transitions (as depicted in Figure 2) has implications for the discourse on actors and agency in transitions. First, for intermediaries, the focus of this book chapter, the literature has seen a broadening of the concept, its meaning and scope of operation from the actor level (e.g., Howells, 2006) to a system level (e.g., van Lente et al, 2003) in recent years which reflects the increasing complexity of innovation and sustainability transitions in the real world. Nonetheless moving from the actor level to the system level conceptually blurs the boundaries between intermediaries and other actors e.g., system entanglers and orchestrators. Empirically, intermediaries are expected to assume characteristics of other types of actors depending on their scope (i.e., actor vs. system level) and mechanism (i.e., directive vs. facilitative) of operation which demands different capabilities, resources and legitimacy. Thus, scholars need to carefully define and motivate the concept they choose to study actors and agency in transitions and reflect on the potential implication including benefits of their choices for example, which characteristics of actors and agency in transitions are highlighted vs. downplayed.

Overall, this chapter proposes several areas for future research on intermediaries in sustainability transitions, highlighting the need to move beyond the current focus on facilitating innovations to explore their role in destabilizing regimes, as well as investigating their impact, power dynamics, and complex reality in an ecology of intermediaries. Such research will deepen our understanding of intermediaries and their contribution to sustainability transitions, enabling policymakers, practitioners, and scholars to better support and facilitate transitions towards a more sustainable future.

Andersen, A.D., Geels, F.W., 2023. Multi-system dynamics and the speed of net-zero transitions: Identifying causal processes related to technologies, actors, and institutions. Energy Research & Social Science 102, 103178.

Barrie, J., Kanda, W., 2020. Building ecologies of circular intermediaries, in: Handbook of the Circular Economy. Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 235–249.

Bergek, A., 2020. Diffusion intermediaries: A taxonomy based on renewable electricity technology in Sweden. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions.

Bessant, J., Rush, H., 1995. Building bridges for innovation: the role of consultants in technology transfer. Research policy 24, 97–114.

Bjerkan, K.Y., Hansen, L., Steen, M., 2021. Towards sustainability in the port sector: The role of intermediation in transition work. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 40, 296–314.

Célia, C., Marie-Benoît, M., 2023. Knowledge and network resources in innovation system: How production contracts support strategic system building. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 47, 100712.

Coase, R., 1937. aThe Nature of the Firm, o. Economica 4, 386–405.

de Vasconcelos Gomes, L.A., da Silva Barros, L.S., 2022. The role of governments in uncertainty orchestration in market formation for sustainability transitions. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 43, 127–145.

DiMaggio, P.J., 1988. Interest and agency in institutional theory. Institutional patterns and organizations 3–21.

Elzen, B., Van Mierlo, B., Leeuwis, C., 2012. Anchoring of innovations: Assessing Dutch efforts to harvest energy from glasshouses. Environmental innovation and societal transitions 5, 1–18.

Geels, F., Deuten, J.J., 2006. Local and global dynamics in technological development: a socio-cognitive perspective on knowledge flows and lessons from reinforced concrete. Science and Public Policy 33, 265–275.

Geels, F.W., 2022. Causality and explanation in socio-technical transitions research: Mobilising epistemological insights from the wider social sciences. Research policy 51, 104537.

Hargreaves, T., Hielscher, S., Seyfang, G., Smith, A., 2013. Grassroots innovations in community energy: The role of intermediaries in niche development. Global environmental change 23, 868–880.

Hodson, M., Marvin, S., 2010. Can cities shape socio-technical transitions and how would we know if they were? Research policy 39, 477–485.

Howell, J.M., Shea, C.M., Higgins, C.A., 2005. Champions of product innovations: Defining, developing, and validating a measure of champion behavior. Journal of business venturing 20, 641–661.

Howells, J., 2006. Intermediation and the role of intermediaries in innovation. Research policy 35, 715–728.

Hyysalo, S., Heiskanen, E., Lukkarinen, J., Matschoss, K., Jalas, M., Kivimaa, P., Juntunen, J.K., Moilanen, F., Murto, P., Primmer, E., 2022. Market intermediation and its embeddeness–Lessons from the Finnish energy transition. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 42, 184–200.

Hyysalo, S., Juntunen, J.K., Martiskainen, M., 2018. Energy Internet forums as acceleration phase transition intermediaries. Research Policy 47, 872–885.

Hyysalo, S., Usenyuk, S., 2015. The user dominated technology era: Dynamics of dispersed peer-innovation. Research policy 44, 560–576.

Kanda, W., del Río, P., Hjelm, O., Bienkowska, D., 2019. A technological innovation systems approach to analyse the roles of intermediaries in eco-innovation. Journal of Cleaner Production 227, 1136–1148.

Kanda, W., Geissdoerfer, M., Hjelm, O., 2021. From circular business models to circular business ecosystems. Business Strategy and the Environment 30, 2814–2829.

Kanda, W., Hjelm, O., Clausen, J., Bienkowska, D., 2018. Roles of intermediaries in supporting eco-innovation. Journal of Cleaner Production 205, 1006–1016.

Kanda, W., Hjelm, O., Johansson, A., Karlkvist, A., 2022. Intermediation in support systems for eco-innovation. Journal of Cleaner Production 371, 133622.

Kanda, W., Kuisma, M., Kivimaa, P., Hjelm, O., 2020. Conceptualising the systemic activities of intermediaries in sustainability transitions. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 449–465.

Kant, M., Kanda, W., 2019. Innovation intermediaries: What does it take to survive over time? Journal of Cleaner Production 229, 911–930.

Kivimaa, P., 2014. Government-affiliated intermediary organisations as actors in system-level transitions. Research policy 43, 1370–1380.

Kivimaa, P., Boon, W., Hyysalo, S., Klerkx, L., 2019a. Towards a typology of intermediaries in sustainability transitions: A systematic review and a research agenda. Research Policy 48, 1062–1075.

Kivimaa, P., Hyysalo, S., Boon, W., Klerkx, L., Martiskainen, M., Schot, J., 2019b. Passing the baton: How intermediaries advance sustainability transitions in different phases. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 31, 110–125.

Klerkx, L., Leeuwis, C., 2009. Establishment and embedding of innovation brokers at different innovation system levels: Insights from the Dutch agricultural sector. Technological forecasting and social change 76, 849–860.

Köhler, J., Geels, F.W., Kern, F., Markard, J., Onsongo, E., Wieczorek, A., Alkemade, F., Avelino, F., Bergek, A., Boons, F., 2019. An agenda for sustainability transitions research: State of the art and future directions. Environmental innovation and societal transitions 31, 1–32.

Lichtenthaler, U., 2013. The collaboration of innovation intermediaries and manufacturing firms in the markets for technology. Journal of Product Innovation Management 30, 142–158.

Löhr, M., Chlebna, C., 2023. Multi-system interactions in hydrogen-based sector coupling projects: System entanglers as key actors. Energy Research & Social Science 105, 103282.

Lukkarinen, J., Berg, A., Salo, M., Tainio, P., Alhola, K., Antikainen, R., 2018. An intermediary approach to technological innovation systems (TIS)—The case of the cleantech sector in Finland. Environmental innovation and societal transitions 26, 136–146.

Matschoss, K., Heiskanen, E., 2017. Making it experimental in several ways: The work of intermediaries in raising the ambition level in local climate initiatives. Journal of Cleaner Production 169, 85–93.

Mignon, I., Kanda, W., 2018. A typology of intermediary organizations and their impact on sustainability transition policies. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 29, 100–113.

Nelson, R.R., 1985. An evolutionary theory of economic change. harvard university press.

Nielsen, K.H., 2016. How user assemblage matters: constructing learning by using in the case of wind turbine technology in Denmark, 1973–1990, in: The New Production of Users. Routledge, pp. 101–122.

Ottosson, M., Magnusson, T., Andersson, H., 2019. Shaping sustainable markets—A conceptual framework illustrated by the case of biogas in Sweden. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions.

Parag, Y., Janda, K.B., 2014. More than filler: Middle actors and socio-technical change in the energy system from the “middle-out.” Energy Research & Social Science 3, 102–112.

Penrose, E., Penrose, E.T., 2009. The Theory of the Growth of the Firm. Oxford university press.

Porter, M.E., 1990. The competitive advantage of nations: with a new introduction. Free Pr.

Rohracher, H., 2009. Intermediaries and the governance of choice: the case of green electricity labelling. Environment and Planning A 41, 2014–2028.

Santos, F.M., Eisenhardt, K.M., 2005. Organizational boundaries and theories of organization. Organization science 16, 491–508.

Smink, M., Negro, S.O., Niesten, E., Hekkert, M.P., 2015. How mismatching institutional logics hinder niche–regime interaction and how boundary spanners intervene. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 100, 225–237.

Soberón, M., Sánchez-Chaparro, T., Smith, A., Moreno-Serna, J., Oquendo-Di Cosola, V., Mataix, C., 2022. Exploring the possibilities for deliberately cultivating more effective ecologies of intermediation. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 44, 125–144.

Stewart, J., Hyysalo, S., 2008. Intermediaries, users and social learning in technological innovation. International Journal of Innovation Management 12, 295–325.

van Lente, H., Hekkert, M., Smits, R., Van Waveren, B., 2003. Roles of systemic intermediaries in transition processes. International journal of Innovation management 7, 247–279.

Weick, K., 1995. Sensemaking in Organizations, vol. 3 Sage.